Here is the presentation and talk I gave at the Homo ex MachinAI conference in Athens on April 12th.

Thanks to Aspasia and Theo for all their hard work organising the conference and for inviting me to speak. Thanks also to the Benaki Museum for hosting such a timely and important debate. I will be speaking as an artist, writer and arts educator who has taught fine art studio practice and contextual studies for many years. I currently run the BA Fine Art and BA Fine Art with Psychology at the University of Worcester where I also lead the Arts and Health Research Group. I won’t be speaking about the latter today, but it informs my perspective on the impacts of generative AI tools on arts education and creativity more generally, particularly in relation to the mental and physical health effects of ubiquitous computing and on-line media environments within which generative AI developed and operates.

This is a list of the kinds of courses taught at a contemporary art school or university. It’s not comprehensive. It could include architecture, game art, interior and spatial design, printmaking, textiles and many others. The point is to show that ‘creativity’ is not a homogenous concept that can be generalised for all the arts. Every art has its own unique history, set of practices, understandings and outcomes. Because of this diversity, generative AI tools will not effect all teaching programs in the same way or to the same extent. Much depends on how teaching is tied to changes within the existing creative and professional fields it leads to.

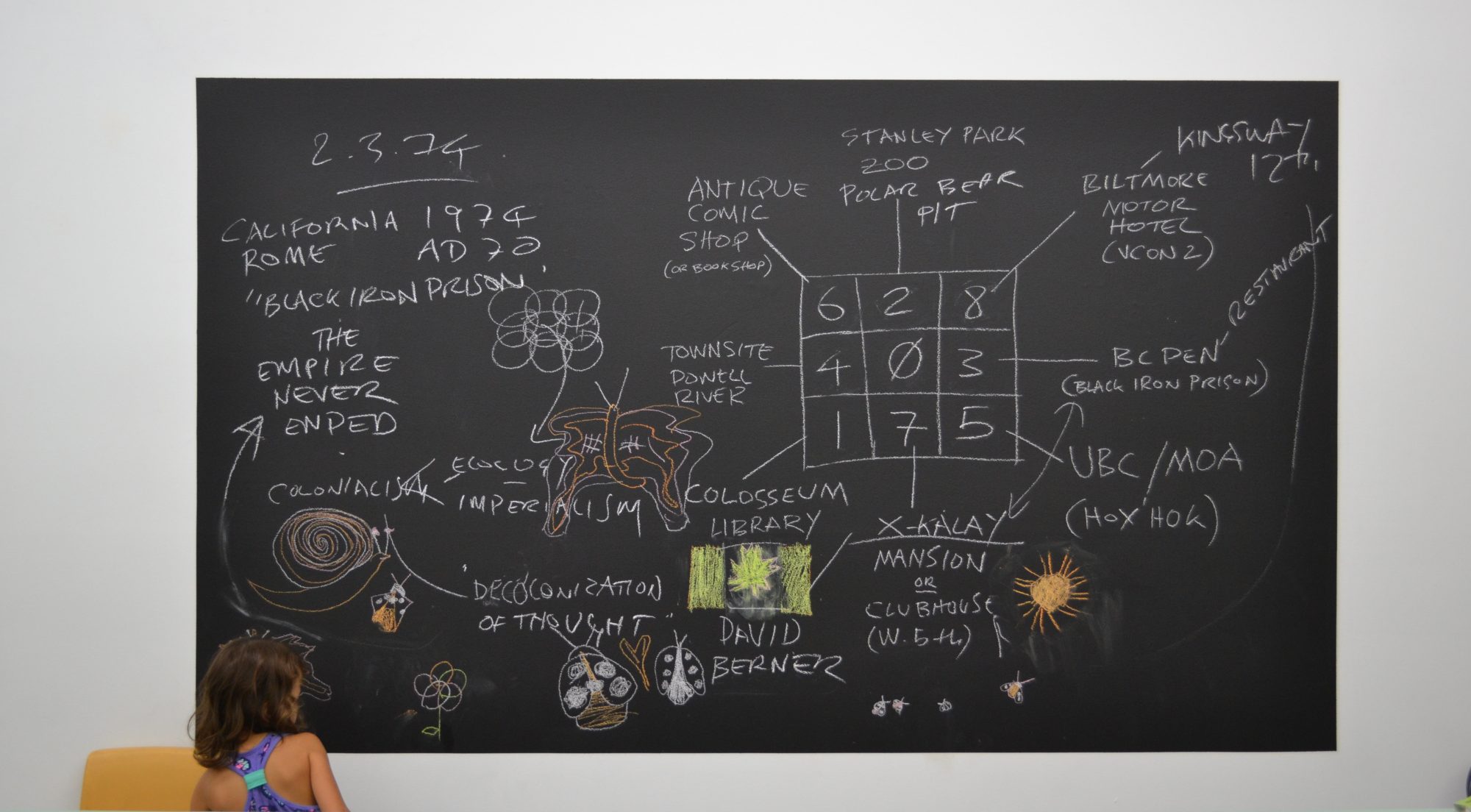

Broadly speaking, teaching for professional fields already impacted by generative AI tools will be shaped most significantly. These include animation, commercial photography, film, game art, graphic design, journalism and marketing. This does not mean that learning traditional studio skills in these areas will become redundant. On the contrary, the successful artistic application of AI tools will depend on the technical experience, cultural knowledge and aesthetic discernment of its users. On the other hand, those arts more closely aligned with manual craft skills, individual authorship and the production of unique, physical artefacts made to be experienced in person, in real time and with all the senses, are less likely to be impacted as rapidly or significantly in the longer term. These include ceramics, dance, fashion, fine art, literature, performance, textiles and theatre.

The use of generative AI tools in an increasingly hybrid teaching environments, a trend amplified by the Covid lockdowns, will however be significant for all our programs. With students now regularly using AI-enhanced learning, research and writing tools, and universities moving towards AI-assisted grading and feedback systems, AI tools will play a transformative role in how teaching, administration and management in Higher Education is conducted, understood and regulated in the near future, regardless of what is being taught. I will be focussing here on my own field: Fine Art. Colleagues teaching in other areas will have their own particular stories to tell.

Continue reading “Generative AI and Arts Education: The Case of Fine Art”