I awoke from the final night of the Ghetto Biennale troubled and sleepless. The events of the last seven days had reached something of a crescendo the previous night and I had spent most of the sleeping hours trying to process the deeply visceral emotions that had laid hold of me. I was awake by 6 am, a habit I had formed while staying at the Oloffson, in order to find a little time, in the one or two hours before the breakfasting guests arose, to be by myself, to write and to reflect on the previous day’s experiences.

Sitting on the terrace I sketched out a list of titles that impressed themselves upon me in response to the feelings that had got under my skin, with view to write them up into a finished text.

It has now been over two weeks since I returned from Haiti and I have struggled to maintain a tangible memory of the feelings that summoned this planned piece of writing, especially in the face of the local, ritual currents persistently over-coding them. So in order to gather my personal reflections of the 2nd Ghetto Biennale as a whole, I will describe, in loose chronological order, the events of the night leading up to this impetus to write. That memory fades is a blessing in the grand scale of things.

But before I begin, I should make a disclaimer about the observations recounted here. They are founded on personal opinion, informed by conversation with colleagues, associates and friends, by much hearsay, gossip and rumour that constitutes the particular ‘tele djol’ of the ghetto biennale, and by ingrained, reactionary reflexes and culturally misplaced hostility. I have clarified several details with colleagues but the opinions expressed here are my own. Moreover, as I try to articulate the sentiments and sensibilities of the event as I experienced them, I feel myself drifting out of context between different audiences. I sense, in the act of writing, an ever-present imaginary authority surveying the text. This phantasm of an authoritative audience is as much, if not more, that against which I write, as that for which I write. The hostility felt and expressed through these lines is directed as much towards a generalised notion of the exercise of authoritative power in the abstract as it is to any real expressions of power exercised consciously, by accident or habit, by any particular individual.

And as I move further into the task of writing, I began to have serious doubts about whether or not it is worthwhile, if it will do any good to express these thoughts. I realise the extreme partiality and subjectivity of my position, of how much of it is based on fragmentary knowledge passed on in private conversation, on strains of barely suppressed and misdirected rage ready to lash out at whatever fantasmatic figures conduct it.

There were moments during the Ghetto Biennale when the re-situating of British cultural politics to the Haitian context became emotionally overwhelming and I was unable to speak without blubbering. I still have not been able to rationalise quite what this was about, and don’t intend to do so. I mention it only to disqualify in advance some of the more reactionary formulations presented here.

The Congress

The final congress of the 2nd Ghetto Biennale was conceived as a summation of the collective experiences of the event as a whole. It took place on the evening of Saturday December 17th in the rotunda in the grounds of the Oloffson hotel. Leah Gordon – chief coordinator of the biennale – had already invited three guest speakers from the established art world of Port-au-Prince to give short presentations about Haitian art in an historical context. It was agreed at a meeting earlier in the week that a selection of participating artists should also give five-minute presentations about their work and experience of the biennale, and that representatives of Atis Rezistans (the sculptors from the Grand Rue area where the Ghetto Biennale takes place), Ti Moun Rezistans (the younger artists from the same area) and members of the Grand Rue community should have a chance to speak too. Initially there had been a plan to run a université populaire in tandem with the biennale but this had become too much to organise along with the other projects taking place. So the congress also became a way to compress the pedagogical plan for the biennale into one event. I knew, well before it began, that this was not going to work. But it was in the spirit of the biennale to give everything our best shot and let fortune take care of the rest. If there was one thing that inspired confidence in public events organised at the biennale it was Rodrigue Ulceana, the stalwart translator, who was on hand to expertly translate between English, French and Kreyol.

The Invited Speakers

The invitation to the three guest speakers had been made with the université populaire in mind. In the two years since the first biennale Leah had grown increasingly aware of the necessity to get the established Haitian arts scene on board. As I understand it, the established art world of Port-au-Prince is organised around a number of private, commercial galleries and collectors in Pétion-Ville, a wealthy suburb on the hills above the downtown area, home to the business, diplomatic and culture elites of the city.

The first official speaker was Axelle Liautaud, an art historian, arts patron and collector with long-standing links to the Centre D’Art in Port-au-Prince. The Centre D’Art is a very significant part of the modern art establishment in Haiti, founded by the American painter Dewitt Peters in 1944. Peters was a Quaker and conscientious objector who had been sent to Haiti by the U.S. Office of Education as part of President Roosevelt’s Good Neighbour Policy, an alternative to World War II military service. The creation of the Centre D’Art led to what has been called the Haitian Renaissance in the 1950’s, a period associated with painters like Hector Hyppolite and Philomé Obin. As a trustee of the Centre Axelle Liautaud is currently co-ordinating the restoration of works saved after the earthquake and the reconstruction of a new Centre D’Art. She began her talk by presenting a small painting by Antoine Obin (Philomé’s son) representing Philomé Obin and Sénèque Obin (Philomé’s brother) in front of the Cap Haitien branch of the Centre D’Art.

By the time the congress began most of the organisers and participating artists were exhausted. Some had been working for weeks leading up to the opening event that had taken place the night before. I could barely stay awake myself. But the film I’d proposed screening and been asked to introduce – Renzo Martens’ Enjoy Poverty III – (originally scheduled as part of the université populaire) had been re-scheduled for the end of the congress at 8 pm. So it looked like I was going to have to sit this through. The pavilion was only booked until 9.30 pm. Any longer and the organizers would have to pay more. It was going to be a long night.

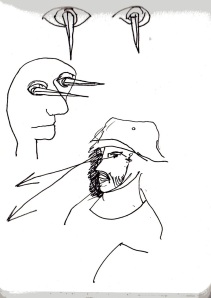

Despite Axelle and Rodrigue’s best intentions the story of Dewitt Peters and the Centre D’Art was lost, at least to me, between translations. Like my colleague Alison Rowe, one of the invited artists sitting beside me, I took to making doodles in my notebook to try and keep myself awake. I looked across at the audience and noticed my colleague Roberto Peyre staring daggers at the panel. I tried to visualize this idea in Atis Rezistans style:

(I learned later that Roberto was himself simply trying to stay awake. That’s how he looks, he told me, when he’s exhausted).

From my right Jana Evans Braziel – a scholar of Caribbean literature at the University of Cincinnati, who is currently writing a book on Atis Rezistans – passed me a written note: ‘Who is the audience? Who doesn’t know this already?’

‘Me’ I replied, and continued with my doodling.

In retrospect this question of ‘who is the audience?’ echoes loudly for this piece of writing. I no longer know who the audience is. There was an audience there, a complex one for sure. Translation was a core issue. With three distinct language communities present any address should have been built with this in mind and have been sensitive to the cultural implications that extend from it. (Accordingly this text, if it were to be addressed to the same audience, should be translated into French and Kreyol). Those of us who had participated in the conference for the first Ghetto Biennale had learned this the hard way, having to reduce our well-planned academic papers into bite-size chunks of clear, translatable English as we spoke. We knew that you needed to keep your sentences simple, short and precise and to expect a five minute talk to last fifteen. But the wisdom did not seem to have been passed on to most of this year’s speakers. Axelle’s talk may well have been coherent and clear on its own terms, but there was no general framing to give the presentation a meaningful context, other than that of the biennale in general.

One of the more complex aspects of working with the ghetto biennale is moving between English, French and Kreyol. Most Haitians speak Kreyol, but few, and mainly those from the elite class, speak French. They are also more likely to speak English, unlike the majority of Haitians. When international artists negotiate their projects with members of the grand rue community they tend to do so in poor French (at least in my case), mediated between the first and second language poles of English and Kreyol. So speaking French to people from grand rue puts the English-speaking visitor in a distinctly trans-cultural position.

The cultural politics of language in Haiti have been described well by Michel-Rolph Trouillot, author of the first book length history of the Haitian revolution written in Kreyol and of the esteemed Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1995):

‘Thus, while it would be wrong to suggest that elites and masses fully share the same culture, it is equally misleading to divide Haiti into two cultural spheres. The fundamental cultural divide is not based on huge differences in cultural repertoire but on the use of those differences that exist to create a social wall that few can cross. Culture works as a divider because of the value added to the rather small part of that repertoire that is not accessible to the majority. More important than bilingualism per se are the number of times an elite child is told not to speak Creole. More important than the elites’ uneven competence in French are the number of times that privileged Haitians make a point of using French, and the fact that the use of French in the school and court systems denies majority participation.’

Michel-Rolph Trouillot ‘Haiti’s Nightmare and the Lessons of History’ (1994)

So the most simple and democratic solution under the circumstances would have been for the invited guests to speak in Kreyol and have it translated into English.

One sentence from Axelle’s talk that registered through the veils of translation with sufficient piquancy to warrant my making note of it, was her claim that the best of the artists from the first Centre d’Art era had stronger personalities than artists now, and that this had something to do with the quality of their work. I thought that this was a weird thing to say given the context of an art event built largely upon the work of Atis Rezistans, many of whom were in attendance. It seemed both rude and snobby.

The 1950’s United States Information Service film about Dewitt Peters and the Centre D’Art (linked above) makes the same kind of statement as Axelle, differentiating between the best and lesser artists in the country. It is something that still gets my goat. It’s not that I don’t recognise that some artists may have a keener aptitude for creating and innovating within certain media than others, that they may be more productive, experienced and consistent. It’s the way the idea reflects and perpetuates a dominant bourgeois model of investment and value in the arts as a measure of artistic exceptionalism, a model which in turn serves the interests of wealthy, cultured collectors. What is at stake here, as it is in other global art worlds, are the gate-keeping roles that those with property and wealth exercise over those without. To quote Willem Schinkel (whose essay I have recently been using to comment on ritual gate-keeping operations in the contemporary London art world):

‘When analysing communication through art, one cannot do without communications by artists, connoisseurs, distributors, dealers, publishers, exhibitioners and the like. All the positions of these actors fulfil gatekeeper functions in the artworld, which is intended here also in the sense of control over legitimate meanings of communications through art. One cannot do without what Bourdieu has called the (struggle over the) ‘legitimate aesthetic disposition’.’

Willem Schinkel ‘The Autopoiesis of the Artworld after the End of Art’ (2010)

What ires me about this situation is that such naturalised, art historical attitudes often operate without the intelligence, wisdom or political awareness inherited from the critical-theoretical traditions of avant-garde and postmodern art history. It is as if the discriminatory impulse annuls the exercise of faculties and values critical of hierarchical mechanisms of power. Bourgeois constructions of excellence within the visual arts perpetually make distinctions between those artists with exceptional talent (and the ambition to mobilise it) and those with only moderate ones and lacking in ambition. This is one of the functions of ritual prize-giving and award ceremonies in the visual arts. Critical intelligence about the arts is welcomed so long as it does not challenge the interests of established wealth, propertarianism and cultural distinction. The attitude tends to encourage a culture of competitive contest, which, when imposed from above, can insinuate itself into the communities in which the artists live and work. I accept that there is a playful and communally valuable dimension to creative competition, but my concern is that emphasising the idea of winners and losers in the long game can amplify latent divisions between individuals in the community and fracture what makes the work of the rue so vital: the fluid, systemic cooperation between individuals in the creation of singular works, that are also parts of a collective community vision. Such divisions have already led to fractures between members of Atis Rezistans in the past.

There is a continuous correlation between collectivism and individualism in the grand rue community which Andre Eugene, founding member of Atis Rezistans and co-organiser of the biennale, would express later in the congress. I paraphrase: “First and foremost Atis Rezistans is a movement in which anyone who wants to can participate, wherever they are. And they can do so as long as they don’t try to lay claim to the movement as their own.”

But I write all this with a high degree of personal discomfort issuing from the unforeseen ethical contradictions that participation in the ghetto biennale brought about. Whether as a visiting artist with a particular political-aesthetic orientation, with one’s own tastes and sensibilities; as a potential buyer, collector or commissioner of works; an informal advisor to visiting curators and prospective buyers; or as a potential future curator oneself, one cannot extricate oneself from the artistic arbitration process and the work of preference and favouritism. What makes one method of aesthetic arbitration more or less valid than another? Is there a mode of evaluation running counter to the privilege of ownership, entitled discernment and unequal exchange that might have long-term practical value in this context? These were the vaporous questions running through my head as I doodled away between the talks.

For better or for worse, I realised that these were not the kinds of questions that were going to be publicly discussed at the congress, let alone formulated and posed between three languages. We were already suffering a severe time deficit and the ambience was sufficiently strained that I doubted anyone wanted to have a public conversation about concerns that would only add more complexity to the already heady and confounding mix of issues weaving through the situation.

Some of us had been trying to avert our hunger and stay awake by drinking rum sours from the Oloffson bar, but this was not proving the best solution. The drinks took too long to order and prepare and are an unaffordable luxury for most people from grand rue. Every fifteen minutes or so I needed to take a walk around the rotunda to keep myself awake. Once in a while I would go out to the local Friendship Bar to buy beers for whoever wanted one.

The next person to speak was Philippe Dodard, a Haitian artist and art historian. According to his Wikipedia entry Dodard has a specialism in pedagogic graphic design. It would have been great to have seen some of this. It’s always a relief to look at images when pedagogical fatigue has taken hold. He began to speak in French which Rodrigue translated into English. Or was it that he began to speak in English and Rodrigue translated into Kreyol? I really can’t recall. He seemed to be switching from one language to another between sections of the paper he was reading. It was a heady method to follow. Beside me, Evel – the artist for whose truck I commissioned the ghetto biennale tap-tap sign – was one of the few people in the audience who seemed to be following closely what was being said. By about the fourth sentence I was thoroughly lost. The talk seemed to be about the differences between modern, neo-modern and contemporary art. Despite a certain level of expertise in the field I really didn’t recognise what Dodard was saying, except in the sense of an historical shift between these formal periods in a specifically Haitian context. The question of what constitutes contemporary art in a contemporary global context is a very important one for the ghetto biennale. It’s a big topic, and one which could only be gestured towards in such a short presentation. It was difficult, in the circumstances, to get beyond ‘whatever was made in its own time is contemporary to that time’. It was also a surprise for someone who lives and works in London to hear Paris described as a centre of the contemporary global art world. I could only assume that the post-colonial legacy of French cultural hegemony still shapes the academic discourse of contemporary art in Haiti.

What was frustrating about the congress in general was the way in which the core critical, art theoretical and geo-political issues that the ghetto biennale poses were being skimmed over rather than engaged in depth. There was not going to be an opportunity like this again any time soon, with so many artists and scholars from different national cultures, all with so much to say about the event, about the art of the grand rue artists, their own practices and the meaning of all this for debates about contemporary art in a global context. And we all gradually began to realise, as the talks ran on, and the allocated time ran out, that this wasn’t going to happen. There was definitely not going to be time to show Renzo Martens’ film. But that was probably for the best. I doubted many of us would have the energy to sit through ninety minutes of Martens’ harrowing exposé of the ethical paradoxes of global aid, photojournalism and contemporary art in the moral labyrinth of ‘humanitarian work’ in the Democratic Republic of Congo. It was a relief when Jason Metcalf, the person running the projector, and another of the participating artists, told me they were not going to be able to show it. It would just have to be re-scheduled somehow.

(As it turned out, I managed to organise a screening of Martens’ film the following day in my room at the Oloffson to an audience of about fifteen participating artists and several people from Grand Rue. It was far from an ideal situation. In retrospect this shunting of Enjoy Poverty off the main stage of the Ghetto Biennale was a lost opportunity to bring some deeply problematic geo-political and contemporary artistic issues to the centre of the event. It would have been controversial and disruptive. But it may have meant the level of critical debate was diverted from the local inter-personal and organisational issues of event.)

When Dodard began to talk about the way contemporary (or was it Neo Modern?) art anticipates the future I was already halfway through a new doodle, and once again thinking, in some oblique, unthinking way about the art of Atis Rezistans, their engagement with the Guédé pantheon, and the inevitability of death as the future for us all. How contemporary can death be?

Andre Eugene – Badji pom Louko (Alter for Louko) (2011)

The rest of his talk was a blur. Maybe I was at the bar.

I was definitely back for the beginning of the next speaker, Babacar M’Bow, an art critic from the African Diaspora Studies Program at the University of Florida, author of Philip Dodard: The Idea of Modernity in Contemporary Haitian Art and a forthcoming book that he announced, straight away, that he was here to plug. (I seem to recall it being called ‘Plugs’. Either I misheard or perhaps it was a joke). His approach was more spontaneous and direct than the other speakers and he seemed to have recognised the need to be concise and to work in short sentences with Rodrigue. I could tell that some of my colleagues took an instant dislike to his brogueish attitude. But at least it piqued their interest in the speeches again.

I couldn’t help notice, as Babacar began to speak, the way that Phillipe Dodard looked at the audience in attendance. Having spent much time on the other side of the speaker’s table, I was probably more sensitive than most to the disciplinary gaze of the invitee. He seemed to be scouring the audience the way a schoolmaster does a potentially unruly assembly. Perhaps he was just very tired too. It perked me up a little, I must say. For a second or two I tried to look my academically conscientious best. But I failed miserably and fell back into my doodles.

Babacar certainly livened things up. And when he mentioned ‘speaking truth to power’ that tripped my attention. Although I associate the term with Michel Foucault, I sensed a different, context-specific meaning in Babacar’s usage. (Interestingly, the expression dates back to American Quakers who, in the 1950’s, used it for the title for a pamphlet proposing a non-violent approach to the cold war). But I did not really understand who or what was allegedly speaking truth to who or what. I inferred that it had something to do with the role of NGO’s in post-earthquake Haiti. I’m not sure. His general drift seemed to be about the very real and apparent poverty of circumstances in which Atis Rezistans live and work, and that the refusal to conceal this fact is what makes the biennale an affront to some. This sounded vaguely on track to me, and I found myself nodding and applauding in agreement, despite being unsure exactly what I was agreeing with (an experience familiar from the working negotiations for my project at the biennale).

One of the more surprising things Babacar said was that the Haitian artist Mario Benjamin should be acknowledged for making the Ghetto Biennale ‘worthy on an international level’. That’s not the story I knew. Quite the contrary. Mario Benjamin, as I understood it, is one of the Haitian art world figures who had been openly critical of the ghetto biennale, in particular the decision to show work in and around Lakou Cheri rather than in more familiar international-style, white-cube type gallery spaces.

Mario is a respected and well-established Haitian artist who was one of the first people to promote the work of Atis Rezistans both locally and internationally. His relationship with the movement is a very personal and complex one. I first met them together at a meeting I had arranged with Jake Chapman in 2008. Mario was very much acting as mediator between Atis Rezistans and the contemporary art scene in London. I can’t quite remember the premise of the meeting. But it had something to do with trying to see what, if anything, Jake might be able to do to facilitate more art world visibility for Atis Rezistans.

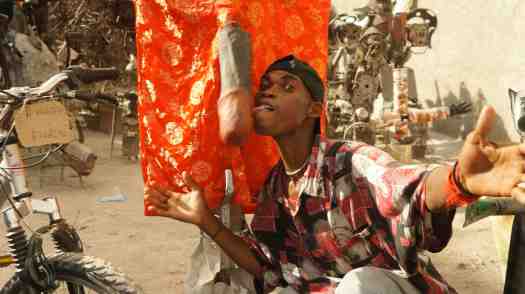

(As you can see from this video Mario has been a strong supporter and promoter of Atis Rezistans in the past. He recognized that few of the major collections of art in Haiti had works by Grand Rue artists – which he considered some of the strongest contemporary art being made there – and he worked to rectify the lack. Mario also used his own success at an international level to promote the work of the grand rue artists. I assume this is what Babacar was referring to.)

Babacar concluded that, in light of the re-building of Haiti after the earthquake, we must begin to ‘reconstruct the language of reconstruction’. This was met with a big round of applause, which I joined in with, before taking leave for a toilet break.

On my way back to the hotel I was approached by one of the grand rue artists I had been working with. He said, as I understood it, that he had something to give me and that he needed to do it somewhere private. I told him that I would speak to him later, that I needed to stay around to screen the Martens film (already an excuse). After a week of negotiations about work, payment and promises, switching between three languages and three currencies (Haitian Gourdes, US Dollars and Haitian Dollars: a non-material currency which has survived from a time when the Gourde was pinned at 5 to the dollar, and one which seems to serve some local calculating function that I never managed to figure) I was starting to get spiky with fatigue. My excuses were becoming less and less plausible. And the weaker they became the closer came the next unforeseen and unpredictable negotiation. I said I would speak to him later in the evening. But I intended not to.

Representation from Atis and Ti Moun Rezistans

When I returned to the rotunda Jana was in the process of asking Eugene and Celeur, as representatives of Atis Rezistans, what their perceptions of this year’s biennale were and what they would like to see happen in the future. Eugene suggested that visiting artists should make long-term commitments to the biennale and begin making plans now for work to be completed in 2013. He also commented on the importance of representation for AR internationally, especially at the Venice Biennale and the Miami and Basel art fairs.

Leah then invited a representative of Ti Moun Rezistans to speak about their experiences of the biennale. It was no surprise that Alex Louis, one of the more ambitious, vocal and confident members of Ti Moun, stepped up to the opportunity. Alex had already spoken a lot at an earlier meeting in which latent grievances about the organisation of the biennale had been openly and frankly expressed. What surprised many of us was that Alex used the platform to criticise some of the invited international artists for being patronising towards the younger artists of the rue, and of having used them to help make their own work rather than engaging in genuine collaboration. It was the first time anything had been said during the congress that touched upon the messy, nitty-gritty micro-politics of the biennale. Even though I thought Alex could have put this in a more gracious and considered way, balanced by some of the more positive experiences of working with the visiting artists (of which there were far more, in my opinion, than negative ones) I did value his intervention. I could see his point even though I wouldn’t have made it myself. I had no idea what had been going on between other visiting artists and the Ti Moun. He may have been referring to my project too. Whatever or whoever he had in mind, it was something of a jaw dropper for many people in the audience. It was the first little cat to be publicly dropped among the friendly visiting pigeons.

The Visiting Artists

Next up were the five-minute presentations by participating international artists. This was far too much for me to take. I had been working with many of them during the week, watching their projects take shape and seeing them finally exhibited the day before. I really didn’t need to see and hear this all over again. I’m sure all the final projects will be filed somewhere in the official Ghetto Biennale website in the near future, and I will be posting some of the work I considered most valuable and interesting here.

I only want to mention one presentation that I caught, luckily, on my way back from the Friendship Bar. That was the presentation by three architects – Vivian Chan, Maccha Kasparian and Yuk Yee Phang – who had been working on plans for an architectural redesign of Lakou Cheri. In retrospect I think this is one of the most important works from this year’s biennale and it represents a level of ambition that I think should be encouraged next time.

The presentation was very professional, with a clearly labeled power point accompanied by a verbal presentation broken down into succinct, translatable sentences. It was amazing what these three architects had managed to achieve in just over a week. Macca arrived the day before Viv and Yuk Yee, and already had the building of maquette of the entire lakou underway with children from the area.

By the end of the week they had liaised with architects already working in Haiti and had plans for a rebuild of Lakou Cheri working almost entirely with recycled materials, that would include a stage, bar and a children’s gallery.

The Assistant Curator

I first heard about the new assistant curator when I arrived at the Oloffson and met Leah on the steps outside. She was about to chair a community meeting in the rotunda about the organisation of the biennale. There was some kind of trouble brewing that had to do with who was taking control of things and how decisions were being made. Apparently she now had an assistant – a PhD student of African Art History and Visual Culture student from Germany called David Frohnapfel – who had offered his services over the internet. I was instantly suspicious, for reasons I will explain, but was glad that Leah had someone to help carry the unwieldy and exhausting burden of organising the visiting artists and associated events. “So if I need to know anything I can ask him, rather troubling than you?” “You can try”, she said.

I met David twice. The first time on my first night in the hotel. The next time I encountered David it was at the planning meeting for the forthcoming opening night of the biennale and the ensuing congress where we were to discuss the spaces artists were to be allotted, the running order for video screenings and the presentations for the congress. By now the word via the tele-djol that David was ‘second in command’ and taking a leading role in all things organisational.

(As it turns out the role of ‘assistant curator’ was intended as a sort of joke between Leah and David. Leah does not consider herself to be a curator but as a facilitator for a complex platform of creative projects. But she was happy for someone to be taking up some of the organisational slack for her. And, according to Leah, David had performed the role of assistant curator admirably for the Nouveau Rezistans show earlier in the week at the French Institute. The joke had been further compounded by an initiative by the artist Cat Barich to make joke identity t-shirts – with names like Curator, Artist, Participant – for various people involved in an earlier press conference.)

After having spent much of the last year in the UK working with direct action groups, being involved with Occupy LSX and participating in several general assemblies, I was acutely aware of how much time is wasted at meetings that are not chaired and moderated effectively or organised according to clear agendas and shared objectives. After such positive experiences of effective collective organisation and planning, the waste of vital opportunities for consensus becomes peculiarly maddening. What was sorely needed for the biennale in general was a simple organisational process, and a dedicated support team with clearly defined roles and responsibilities. Some basic consensus decision-making techniques would have gone a very long way there. Seeing the organisers and their assistants arriving at the final planning meeting for the main event without pens and paper, laptops or maps of the lakou did not bode well.

Another important theme within the contemporary anti-cuts movement in the UK is a naturalised culture of voluntary/mandatory labour practices which have a particular role in the arts where unpaid labour in privately funded art institutions is often confused with unpaid labour that artists embrace as the necessary ontological risk of the ‘work’. In the former case, interns are often exploited in the interests of their CV’s, which, they assume, will help them find paid work in the future. Such practices explicitly exclude from the volunteer art world people who do not have the kind of material and cultural capital that gives them the confidence to operate in such environments for free. It is both an exclusionary and exploitative practice that aligns the ‘exceptional economy of art’ (Abbing) with the economic advantages of running art institutions on unpaid labour, while consolidating the cultural capital of those who already have it.

So two bêtes noirs came together for me in the figure of the assistant curator: the ambitious but inexperienced administrator and the careerist, CV-orientated ‘volunteer’ curator. If only I’d known it was a joke, I might not have become so hot under the collar about it.

I mention all this as a backdrop to explain my reaction to what happened after the artist’s presentations. Leah invited anyone who felt the need to respond to Alex’s earlier comments about collaborating with visiting artists. Surprisingly it was David who took the opportunity, accusing some of the boys of Ti Moun Rezistans of sexual harassing several of the visiting women artists. He said something like: “Perhaps if you hadn’t spent so much time asking them whether they had boyfriends, if they were married, and going on and on about your zo-zo’s [Kreyol for dick] perhaps they might have been more inclined to work with you”.

Now I was flabbergasted. I couldn’t believe he’d said that. I was incensed. Who the fuck did he think he was? Self-ingratiating Johnny-come-lately, non-curator dick. How dare he?

What upset me was a compound thing. In part it was my prejudices outlined above. It also had to do with conversations I had been having during the biennale with several people about the systematic state-sanctioned subjugation of Black youth that is reaching new levels of intolerance in the UK, where the youth are more extremely alienated by state violence than those of grand rue. I know these things are not directly related. But in my mind they are. So the rhetoric of an older, white, culturally and economically privileged male speaking out publicly against black youth in the interests of middle-class women who have chosen to come and work with a community they do not know, pushed my buttons pretty badly.

And what made this accusation all the more amazing was that the public face of Grand Rue art, Atiz Rezistans and the Ghetto Biennale, is big bouncing dicks and skulls. That’s what they’re famous for. Take a look at the work exhibited at the Venice Biennale. The show was called Death and Fertility. A big dick is the first thing you see when you arrive at Lakou Cheri. So to accuse the young men of being zo-zo-centric seemed a bit absurd in the context. You would have to be pretty blinkered not to recognise the blatantly erotic and sexual nature of much of the exchanges that take place in the rue and back at the hotel. But I guess this is ok if it’s the older guys who are doing it.

I’m not trying to defend the young men of Ti Moun if they were insulting to the visiting women artists. It was an issue of who took the role of defender of their virtue in this particular context.

The Zo Zo’s of Iron Men

After a spirited defence of her work and her feelings about being part of the biennale and collaborating with Ti Moun Rezistans by Esme Anderson, and a call from the photojournalist and human rights advocate Gina Cunningham-Eves to replace Alex Louis’ computer, which had been stolen the night before, we thought it was all over and that we could, at last, retire to the bar and to bed.

But it was not to be. Gail, a woman who was at the Biennale chaperoning her daughter Whitney (a student of Caribbean art and literature from the University of Tulane) stepped up and took the microphone. This was not on the program. She then unfolded a piece of paper and explained, via Rodrigue, that she wanted to read a letter that the pastor of the Presbyterian Church of which she was a member – the biggest in North Carolina apparently – had written to the young people of Grand Rue. “How many of you kids out there have your blue bangles on?” she asked. To my horror most of the children who had been playing in and around the rotunda during the congress raised their arms. Sure enough, most of them had on one or more of the blue rubber wrist straps. She began to explain that these bangles represented a commitment to Jesus through a mission that her church had initiated called the Iron Men’s Ministry.

Apparently she had made a connection between the men made out of iron by the grand rue artists, and the iron men of said ministry.

At this point I was on the verge of standing up and shouting at her to stop. I was going to accuse her of child abuse. But looking round I could see that most people weren’t taking any notice of her and those that were, were as gob-smacked as myself. The academic up-town delegation had already retired to the Oloffson bar.

As soon as she was finished I knew what to do. I rushed over to Jason and asked him to play a track that had become a minor anthem amongst some of us at the biennale, and one that we knew could get a party started (not that it ever took much). It was all I could think to do as a retort to Claire and her iron men.

So the last stage of the congress, for those of us who were still left, was dancing with the children from grand rue, and their blue bangles, to Major Lazer’s ‘Pon Da Floor’.

On my way back to the hotel, after packing up the cinema and clearing the rotunda, I was approached once again by the artist who had said he had something for me. I was too tired and exhausted to argue. He led me by the arm, out of earshot of the crowds gathering at the terrace, towards the pool. He began to explain that a member of his family was very ill and he did not have enough money to take them to hospital. “How much do you need?” I asked. “About $50 US” he said.

I stared past him towards the famous Oloffson swimming pool where I often imagine the body of Dr. Philipot, the secretary of social welfare who killed himself in Graham Green’s The Comedians, still floating. Instead I could see the children from the grand rue getting ready to have a swim. But something was stopping them. I followed their gaze. In the pool, against the north-facing wall were two figures, a white female and a young black male, making movements that meant only one thing. For a moment I wanted to get closer and find out exactly who it was. But no. I really didn’t need to know.

My new friend was still waiting for a response. I felt as guilty for doubting his story as anger at the thought of it being a scam. I was simply very tired and wanted to go to bed.

I gave him the remaining two thousand gourdes in my pocket and wished him the best.

Above everything else that happened on the night of the congress, it was something in the way I gave him the money that kept me from sleeping.

Wow!!! that’s one of more direct comment i read about the biennaly

Hi Romel, yes. It was tough to write too. But glad you read it. Hope all cool with you. Hope to see you in 2013!

coach sale

informative, thankyou

x hernandez