Update from Emergency Meeting at Gasworks, Sunday Jan 24th

Following last week’s meeting to coordinate solidarity action with Haiti we established a working group called the ‘Haiti-London Konbit’. We have set up a list-server with Indymedia where people can post information about upcoming events. Just add your email address and any mails you send will be distributed to the other members of the the group.

Konbit is a traditional form of cooperative communal labour in Haiti, whereby the able-bodied folk of a locality help each other prepare their fields. Haitian peasants, as a rule, have a small plot of land to themselves that they use for subsistence (they feed themselves and their family from it). Otherwise, the bulk of their work is sharecropping, a form of feudal slavery, whereby they work for a landlord who takes the lion’s share of their produce. Konbit involves weeding, stone removal, planting, sometimes even the harvest. It is a time for solidarity and cooperation in the face of adversity and usually involves a feast offered up by the recipient of the help (thanks Andrew Taylor from the Haiti Support Group for this definition).

Most of the people present at the Gasworks meeting agreed that there is a widespread lack of awareness about the basic facts of Haitian history. Even people with an interest in the country are unaware of how and why Haiti became such an economically impoverished nation. The next post on the blog will be a very brief history of Haiti and its Debt. In advance of that post here is something an article on the issue of Haiti’s debt from the PAPDA (Haitian Advocacy Platform for Alternative Development) website and Hilary Beckle’s article The Hate and the Quake.

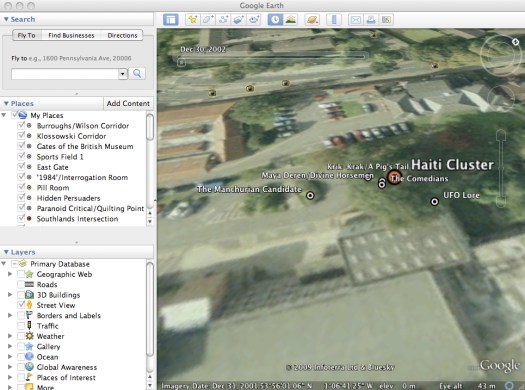

We would like to develop a Web 2.0 video version of the story of Haiti’s debt (possibly in collaboration with artists from the Grand Rue) to circulate on the internet. We will be discussing the logistics of this at the Free School event.

During the meeting at Gasworks we began a discussion about the legitimacy of the language of ‘debt’ in the context of Haiti and the racist misrepresentations of post-earthquake Haiti being on the edge of anarchy. I expect there will be more to discuss on these issues at a later date. But in the meantime here is an excellent and well-hyperlinked article on language of ‘looting’ in the journalistic response to the earthquake in Haiti by Rebecca Solnit.

There seemed to be strong support for the idea that what we are witnessing in Haiti is an example of ‘disaster capitalism’ as defined by Naomi Klein, and that the media focus on ‘looters’ and ‘rioters’ was a significant component the ideological apparatus being used to justify the presence of tens of thousands of US military personnel on the island. John Pilger has written an incisive riposte to the militarization of the aid effort in Haiti and parallel media reports about ‘criminal mayhem’ for the New Statesman. Peter Hallward’s recent article for Monthly Review is also very good in this context, arguing that the current US presence in Haiti amounts to a third military occupation.

Update on the best organizations to donate money too

Although some aid is now starting to get through to communities in Haiti, more than three weeks into the massive aid program there is still a severe bottleneck on the resources and the majority of the population have still seen seen no assistance. Leah Gordon has reported that an unofficial zoning system has been put in place by the military authorities divided into green zones, where relief can pass freely, and red zones which have restrictions placed on them. The Grand Rue area for instance is in a red zone, as are many of the poorer neighborhoods in Port-au-Prince. Democracy Now addressed the problems of aid distribution to the red zones here.

Flavia Cherry, chair of the Caribbean Association for Feminist Research and Action (CAFRA) has reported that the major aid agencies have done little to prioritize aid for the most needy member of the population and that it is obvious that the agencies are unable to handle the scale of the problem on the ground there. She questions why Caribbean governments are not being allowed to play a role in the operation despite many willing volunteers who can speak Creole and are ready to take aid directly to the most needy populations.

Ryan McCrory, Co-Director Haitian Sustainable Development Found, reported his recent experiences with the aid distribution program to the HSG. The large NGO’s require communities to fill out a 100 question form in order to receive aid. These forms can take as long as a week to complete. Of particular difficulty is explaining directions to locations in a city reduced to rubble by the earthquake. The Haitian government is being entirely bypassed in this operation and small organizations have completely given up trying to work with larger NGO’s and the UN because there has still been no sign of their goods being released. Instead they are traveling to the Dominican Republic to buy food and medical provisions..

I have been in regular email contact with Charles Arthur of the Haiti Support Group. The following is a summary of that discussion.

The Haiti Support Group (HSG) has circulated an important statement from the Coordinating Committee of Progressive Organizations presenting an overview of the current situation which can be found on Norman Girvan’s website.

Following this statement the HSG are now concerned that such is the international response to the many Haiti emergency appeals – i.e. so much money has been donated – that those organisations running the appeals will be in a position where they cannot distribute/use the money quickly or in a way that reaches the more marginalised people/organisations. They are concerned that many organisations in Haiti that are working with marginalised people but don’t have good international connections are not going to get any financial assistance. In this context you might consider making your funds available to the HSG for it to distribute to less well-known but equally deserving grassroots organisations. The HSG would match any tax relief that you would have got by donating to the big humanitarian agencies.

The best way to send money to the HSG is by direct bank-bank transfer, details as follows:

Payee name: Haiti Support Campaign

Payee account number: 6 1 7 2 0 9 4 1

Payee sort code: 6 0 – 0 3 – 3 6

Alternatively you can send a cheque to;

Haiti Support Group

c/o Leah Gordon

10 Swingfield House

Templecombe Road

London E9 7LX

The entirety of donations will be divided in three equal parts and sent as soon as possible to the following:

KOFAVIV is a women’s organisation that for many years has been working with women in the poorest and most marginalised communities in Port-au-Prince. It provides a space for women to meet, medical care for victims of rape, sexual violence, and other violence, advice on legal issues, and many other forms of practical and moral support to women who otherwise would get no help at all. It was the only organisation in Haiti that publicly denounced the rape and sexual violence committed by the gangs that controlled various shanty-towns in Port-au-Prince in the 2004-6 period. KOFAVIV lost its office in the quake. Many core members lost their homes and are now living on under plastic sheets in the main square in the capital. From there, they are trying to continue to provide help to other women.

Batay Ouvriye is a workers’ organisation which since 1995 has been helping factory and plantation workers to organise themselves to win improvements in wages and working conditions. It is one of the few active and effective workers organisations in the country. In Port-au-Prince the core members are providing relief and assistance to the best that their limited resources allow at the Batay Ouvriye centre in Delmas 16. Workers who have lost everything – their jobs, their homes, their spouses and children, and families which have lost their ‘bread-winnner’ are getting help from Batay Ouvriye but the organisation desperately needs financial assistance. It has a few links with organisations abroad but not with any which have large resources to be able to make sizeable donations.

The PAPDA/POHDH plus 4 organisations are some of the most effective Haitian progressive organisations working with the majority population on issues of participatory democracy, the economy, human rights, education, communications, etc. The two platforms and four organisations – many of which lost their offices in the quake – have set up a coordinating committee to pool resources and organise joint responses to the disaster. They have opened a centre in Canape Vert to provide medical and material assistance to survivors. They plan to open more of these centres in areas of the city that are more or less ignored by the large humanitarian agencies.

PAPDA has set up a bank account for the purpose of directing material contributions to the organizations it works with:

PAPDA BANK ACCOUNT FOR CHANNELING SOLIDARITY SUPPORT:

Account Name: Camille Chalmers and Marc-Arthur Fils-Aimé

Account Number: 130-1012-457066 (checking account)

Bank Name: Unibank SA, Port au Prince, Haiti

Swift code: UBNKHTPP

UniBank has many accounts to receive money in Euros or U.S. dollars:

1) At Wachovia bank in New York (BIC Code: PNBPUS3NNYC. ABA / Routing: 026005092). The account of the UniBank there is: 2000192002189

2) At Société Générale, 1221 Avenue of the Americas New York (BIC Code: SOGEUS33. ABA / Routing: 026004226). The account of the UniBank there is: 194,980

3) At Société Générale, Paris la Defense Cedex 92,972 France (BIC Code: SOGEFRPP. Count UniBank there in Euro: 003-01-50607-0 IBAN: Fr 7630003 06990 00301506070 53)

4) In Bank of America, London England (BIC code: BOFAGB22. UniBank Count in euro: 6008 23805023 IBAN: GB33 BOFA 1650 5023 8050 23. In sterling account: 6008 23805015 IBAN: GB33 BOFA 1650 5023 8050 15

5) Banque Nationale du Canada International Commercial Operations, 1010 Rue de la Gauchetière Ouest, Suite 750 Montreal PQ Canada H3B 5K7, BIC Code: BNDCCAMM. Count UniBank there: 097608-236-001-001-01 (Dollars canadieneses) 097608-240-002-001-01 (USD)

6) In Banque Royale du Canada, 180 Wellington Street West Toronto, Ontario M5J 1J1 Canada – BIC Code: ROYCCAT2. Account UniBank d ela there: 09591-406-583-5 (USD) / 09591-390-111-3 ($ CAD)