This video was shot during the 2nd Ghetto Biennale in Port-au-Prince, Haiti in December 2011. It documents the painting of a sign I commissioned for a special Ghetto Biennale tap-tap truck, intended to promote Ti Moun Rezistans’ Tele Geto project during the event.

Talks about the Zombie Metaphor

I will be giving two talks on the subject of ‘The Zombie Metaphor‘ as part of the upcoming Kafou: Haiti art and Vodou show at Nottingham Contemporary. On Tuesday 6th November I will be introducing a zombie double-bill of White Zombie (Victor Halperin, 1932) and Dawn of the Dead (George A. Romero, 1978), and on Wednesday I will be part of a panel discussion with Mark Fisher (Capitalist Realism, 2009) and Carl Cederström (Dead Man Working, 2012).

I will be giving two talks on the subject of ‘The Zombie Metaphor‘ as part of the upcoming Kafou: Haiti art and Vodou show at Nottingham Contemporary. On Tuesday 6th November I will be introducing a zombie double-bill of White Zombie (Victor Halperin, 1932) and Dawn of the Dead (George A. Romero, 1978), and on Wednesday I will be part of a panel discussion with Mark Fisher (Capitalist Realism, 2009) and Carl Cederström (Dead Man Working, 2012).

Humanitarian Violence 2: Night of the Celebrity Saviours

Beware, of his promise,/Believe, what I say

Before, I go forever/Be sure, of what you say

So he paints a pretty picture/And he tells you that he needs you

And he covers you with flowers/And he always keeps you dreaming

If he always keeps you dreaming/You won’t fear the lonely hours

If a day could last forever/You might like your ivory tower

But the night begins to turn your head around/ And you know you’re gonna lose more than you’ve found

Yes, the night begins to turn your head around

The Night – Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons

What if we took Jason Russell’s mission to ‘Cover the Night’ with Joseph Kony posters literally? Let’s take ‘the night’ in its poetic, metaphorical sense as a time of darkness, fear, illicit freedoms, predatory, carnal animality, ‘the dark night of the human soul’, and all that, and then imagine covering up this terrible dark space with endlessly duplicated, Warholesque pictures of a mass murderer.

Not a bad image really. Fair play to ‘em!

A recent editorial in Black Star News makes a last minute plea for Invisible Children (the organization founded by Jason Russell which produced Kony 2012) to call off it’s ‘Let’s Cover the Night’ plan. At a forum at New York University’s School of Law Victor Ochen asked how Americans would feel if some organization had decided to make Osama bin Laden famous by wearing bin Laden T-shirts and plastering the streets with posters to promote a military campaign to capture or kill him. As we well know, the US government didn’t need the pressure of a viral marketing campaign to get that job done. But this should not obscure the parallels between the mission to terminate both commands. A recent article in the Washington Post reports from the newest US military outpost in the Central African Republic where US Special Forces – Russell’s euphemistic ‘advisors’ – are already, allegedly, well on Kony’s case.

“The Americans have captured Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein,” a local tribal chief told the journalist “Surely they can catch Joseph Kony.”

There is, understandably, some scepticism about the US military presence in the region and the actual reasons for it. “The LRA has reappeared,” said Martin Modove, the head of the Catholic diocese in Obo. “The presence of the Americans has not changed anything. We just see the Americans driving or walking in town. We don’t see what they are doing to catch Kony.”

Oh dear. This does sound familiar. Some of you may recall the arrival of the US military in post-earthquake Haiti and how, as an Al Jazeera news report put it five days after the quake, ‘Most Haitians have seen little humanitarian aid so far. What they have seen is guns, and lots of them’. And not much has changed since then.

What we see in both the Kony 2012 mission and the militarization of aid in post-earthquake Haiti is the strategic manipulation of collective human sympathy towards the suffering of others as a pretext for US military intervention in countries with strategic and/or military-economic value. In October last year President Obama announced he would be sending US Special Forces on a ‘humanitarian mission’ to help defeat the LRA. US troops will only use their weapons in ‘self defence’ or, in what amounts to the same thing, in protection of the ‘national security of the United States’. Kony’s threat to the US has nothing to do with his treatment of child soldiers or the murder, rape and kidnap of thousands of civilians. It is being used as a moral pretext to divert attention from the real reasons for being in the region: the strategic economic value of Africa as a continent and the need to challenge China’s territorial control of the resources there. John Pilger has described this as part of a new ‘Scramble for Africa’.

In his article KONY 2012 and The “White Man’s Burden” Revisited Amii Omara-Otunnu draws parallels between the logic of the Kony 2012 mission the 19th century, overtly colonial, proto-NGO’s.

‘The European NGOs of the period, such as Christian missionaries, chartered commercial companies and geographical explorers, astutely manipulated the ignorance and sense of compassion among Westerners to evoke pity for Africans and in the process provided pretext, justification and support for European powers to intervene in the continent.’

‘The gist of the potent public relations strategy used by European NGOs in the nineteenth century was that European powers needed to intervene in the continent for humanitarian reasons. One compelling “humanitarian reason” retailed at the time was to abolish the slave trade and ameliorate its evil impact.’

‘What, of course, transpired as a result of the various campaigns by European NGOs in the nineteenth century was that European powers met in [sic] Berlin Conference from November 1884 to February 1885 to work out the ground rules for dividing up Africa among themselves, without due consideration of the interests of African peoples.’

The parallel strategies of Kony 2012 and the 19th century NGO’s include: directing attention towards the victims rather than the long-term, macro-political causes of their suffering; manipulating the ignorance, sentimentality and sense of compassion of people in the West in order to profit from the misery of Africans; giving the impression that primary agents in these missions are motivated by altruism rather than self-interest; and combining an image of a diabolical ‘inhuman’ tyrant with the suffering of Africans in general in order to justify imperialist military intervention in the country.

Such parallels may in part account for the fact that at some of the screenings of Kony 2012 in Uganda viewers pelted the screen with stones: a bizarre symbolic fulfilment of Jason Russell’s initial inspiration to go to Uganda in the first place.

CELEBRITY SALVATION

It is perhaps not surprising that Jason Russell’s thespian background would make him a big fan of the celebritariat. We could even see Kony 2012 as a sort of substitute for the genocide musical he never got to make, with his 20 ‘culture makers’ as the cast, and 12 policy makers as the backers. But there’s no more ‘waiting to be discovered’ for Jason now. There does however seem to be some dark psychology at work in Kony 2012 and the plan to ‘Make Kony Famous’. The scene where Russell tries to explain to his son the difference between the nice, good little boy – ‘just like you!’ – and the ‘evil man’ who makes little boys – ‘just like you’ – do horrible things to other little boys – ‘just like you’ – is particularly psycho. I can’t help imagining Kony’s face staring back at Russell in the mirror of his darkest dreams, the faces alternating with increasing frequency (Good Dad/Bad Dad, Good Dad/Bad Dad, Good Dad/Baghdad, Good God/Bad Dad, God Good /Dad Bad) until the face of Kony replaces his own and stares back at him, learing, Hyde-like.

Equally enjoyable in terms of this dark fantasy is the video for another of his Invisible Children projects – The Fourth Estate – a video invitation to join the new revolution. In it Kony…I mean Russell…speaks of “a new Liberty, a new Right, a Citizenship founded on the belief that all men and women in the world are created equal.”. As he speaks a faceless, silhouetted and sharply-dressed executive-type gently touches one photo on a wall of mug-shots of twenty-somethings with the their faces obscured by the word ‘Uninvited’ (Imagine the horror of not being able to take part in this world-changing fun-fest of diabolical despot terminating! Un-endurable.) In this new world, “Justice for all is not a fantasy”. Cut to the faceless deliverer of the new constitution/party invitation being chauffeured in a very expensive-looking, super-shiny-black sports-limo: “A generation that will pursue the world’s worst criminals, no matter where they hide, or who they kill, and bring them to justice. It is the future. Some of us are not ready. Most of us fear the change. Others see what could be and what is waiting to be made”. World-changing, wax-sealed letter arrives at a surprisingly skanky- looking doorway. As the letter is opened the voice tells us “The time has come for a new estate”. On August 2011 a new revolution will be mapped out. And you are invited to be part of it. Cut to shabby young man in a hoodie walking into the blinding limelight of a cinema auditorium. “You will say it all began at the Fourth Estate. Because it will’.

You shall go to the ball.

The ‘viral success’ of Kony 2012 owes much to its celebrity endorsements. As demonstrated with the immediate aftermath of the earthquake in Haiti, celebrities are quick to use the power of their fame and wealth to ‘raise awareness’ of the suffering of poor people in far off countries. A list of the top celebrity donors, the causes they give to, and – for those with strong stomachs – a catalogue of drearily predictable, sentimental slush videos can be found at Look to the Stars – The World of Charity Giving.

As George Clooney, A-list socially conscious celebrity, and one of Kony’s…I mean Russell’s…20 ‘culture makers’ put it in the video: ‘I’d like indicted war criminals to enjoy the same level of celebrity as me. That seems fair. That’s our objective. It’s to just shine a light on it’.

That Clooney and Russell apply the same theatrical metaphor of the limelight is telling here. There is, I think, a fundamental relationship, which I won’t expand any further here, between the ‘banality of sentimentality’ proposed by Teju Cole, the ‘Hello-magazine effect’ (i.e. the illusion of easy-access meritocracy generated by celebrity culture) and the popular, youthful, utopian, humanitarianism exploited by Kony 2012.

This is explicitly the case in Haiti, where US imperialism, disaster capitalism and Evangelical missions are inextricably linked. How precisely the celebrity saviour complex fits in with these processes will need to be addressed in a later post.

The White Saviour Industrial Complex would be an excellent placeholder for these themes, except that the celebritariat is not an explicitly white machine. In the case of Haiti, although Bradd Pitt and Angelina Jolie were first off the celebrity doner starting blocks – followed up by Madonna – Wyclef Jean, Oprah Winfrey and Tiger Woods were hot on their heels.

I’m not explicitly criticizing any of these individuals and their motives for wanting to raise awareness and revenue to fight for their pet humanitarian causes. What’s more interesting is how the deeper psychic mechanism of fame is mobilized for popular humanitarian causes, how this mechanism recursively endorses celebrity culture in general, perpetuates magical-thinking on the part of charity givers that their donations will actually lead to a reduction in the amount of real human suffering and diverts popular consciousness away from the real political and economic causes of that suffering.

Putting celebrity mass murderers in the limelight only casts the imperialist military-economic strategy of the US into deeper obscurity. And this is something that Evangelical Christian organizations, of the kind that Russell is personally involved in, have a fundamental role in.

Humanitarian Violence 1: Making Kony Famous

‘The banality of evil transmutes into the banality of sentimentality. The world is nothing but a problem to be solved by enthusiasm.’ – Teju Cole

I’m currently trying to compose a text arguing that the US militarization of aid following the earthquake in Haiti was an act of religious violence. Whether or not it will ever be finished remains to be seen. In the meantime, and on a related thread, a very interesting case of viral humanitarian violence is currently gaining a lot of media attention, not least since its director Jason Russell had a very public brush with insanity recently. I must admit, on seeing the author of Kony 2012 loose the plot in such a spectacular fashion, I suspected he had probably been ‘pwened’ by the man he has made it his mission to bring to justice: Joseph Kony, leader of the Lords Resistance Army. Russell is certainly messing with some serious dark spiritual matter here.

I won’t labour a critique of the film itself and the viral social media methods used to spread the mission. Teju Cole’s article The White Saviour Industrial Complex does an excellent job of that.

But I will quote a little from the film, to help frame the general thesis linking the ‘White Saviour Industrial Complex’ with the militarization of post-disaster, humanitarian aid. Here’s the voice of Jason Russell, telling us what we need to do to bring the mass murderer to justice:

“It’s hard to look back on some parts of human history [cue picture of Hitler and death camp] because when we heard about human injustice we cared, but we didn’t know what to do. Too often we did nothing. But if we’re going to change that, we have to start somewhere. So we’re starting here, with Joseph Kony. Because now we know what to do. Here it is. Ready? In order for Kony to be arrested this year the Ugandan military has to find him. In order to find him they need the technology and training to track him in the vast jungle. That’s where the American advisers come in. But in order for the American advisers to be there the US government has to deploy them. They’ve done that. But if the government doesn’t believe the people care about arresting Kony the mission will be cancelled. In order for the people to care, they have to know. And they will only know if Kony’s name is everywhere.”

So, in order to ‘Make Kony Famous’ 20 ‘culture makers’ – ‘celebrities, athletes and billionaires’ – will ‘use their power for good’ to make Kony ‘a household name’, and 12 policy makers will use their authority ‘to see Kony captured’. In other words the plan is to mobilize millions of young, optimistic, netizens, and a select group celebrities and politicians, to lobby the US government to continue and intensify the US military presence in Uganda.

‘So we’re making Kony world news by redefining the propaganda we see all day, everyday that dictates who and what we pay attention to’.

In with your Kony 2012 guerrilla marketing ‘action kit’ are two bracelets (“one for you, and one to give away”) with a unique ID which, when inputted to the net, plugs you into the ‘Make Kony Famous’ mission program and enables you to ‘geo-track your posters and track your impact in real time’.

I should have known by the bangles that there were covert metaphysical powers at work here. Those of you who attended the conference of the second ghetto biennale may recall Gail, the woman from North Carolina, who infiltrated the biennale under the pretext of accompanying her daughter to event, while she was in fact on a mission from the Iron Men’s MENistry to save the innocent souls of poor black folk by distributing bangles to the children of the Grand Rue. What is it with Evangelical Christians and bangles?

It seems to have taken none other than the brilliant Charlie Brooker to expose the secret evangelical conceit behind Jason Russell’s fame-blitz on Kony. At a recent lecture at the Christian Liberty University in the USA Russell explains how ‘the trick is not to go out into the world and say “I’m going to baptize you, I’m going to commit you, I’m going to win you over”. Your agenda is to look into the eyes, as Jesus did, and say “Who are you?And will you be my friend?”‘

The son of founders of the Christian Youth Theatre, Russell was inspired by the story of British photojournalist Dan Edlon, stoned to death by an angry mob in Somalia in 1993, to travel to Sudan with the dream of documenting a genocide in the style of Moulin Rouge, Chicago or Hairspray.

In an recent program on Democracy Now Victor Ochen, a survivor of the LRA and director of African Youth Initiative Network, explains how he showed the Kony 2012 video in Uganda to 35,000 people who had no way of seeing the film over the internet and questions both the wisdom and likely effects of the Kony fame blitz.

Today (April 20th) is ‘Cover the Night’ day, when Jason Russell’s army of fame-makers plan to blanket ‘every street in every city’ with the specially designed Shepard Fairey posters of Joseph Kony. There is still hope. Tell everyone you know.

This is contemporary global people power!

“Lets have fun while we end genocide!”

Mis-Attribution

This is a short post to correct a mis-attribution of a photo of André Eugène’s ‘Badgi Pom Louko (Altar for Louko)’ (2011) to myself in Nadine Zeidler’s recent review of the biennale in Frieze. I took the photo but the work is very much Eugene’s (with contributions from Michel Lafleur, one of the tap tap sign painters). The photo is relatively high-res. The details are well-worth a closer look.

New Tap Tap Film from Haiti

I just came across this exciting new serialized film called Tap Tap made by Zakmel Films (director Zaka, producer Melanie Reynard, director of photography Germain Jn. Luccere). The film will be subtitled soon.

There’s more information about the film on Youtube and at the Facebook site.

Disaster Capitalism in Haiti – Two Years after the Quake

“We also know that our longer-term effort will not be measured in days and weeks, it will be measure in months and even years” – President Obama, speech announcing the establishment of the ClintonBush Haiti Fund, January 16th 2010

Okay, so it’s almost two years now. Let’s take a look at the long-term effort.

If anyone was in any doubt that the Haitian earthquake was going to be a goldmine for the disaster capitalists, a recent article at Counterpunch – which accounts for where the money raised for disaster relief and reconstruction ‘did and did not go’ – makes for a sobering, and frankly depressing read.

‘Two years later, over half a million people remain homeless in hundreds of informal camps, most of the tons of debris from destroyed buildings still lays where it fell, and cholera, a preventable disease, was introduced into the country and is now an epidemic killing thousands and sickening hundreds of thousands more. Haiti today looks like the earthquake happened two months ago, not two years.’

Here are some of the starker facts figures about where the money went and who was consulted about it:

- 33% of every dollar of US aid went to the US military

- only 1% of the $3.6 billion raised by donors went to the Haitian Government

- less than 1% of the $412 million in US funds allocated for infrastructure reconstruction in Haiti has been spent by USAID and the US State Department

- international aid coordination meetings were not translated into Kreyol

- the Haiti Neighborhood Return and Housing Reconstruction Framework drafted by the Interim Haiti Redevelopment Commission (IHRC) which was supposed to guide reconstruction, was not published in draft form in Kreyol so local people could review it

- of the 1490 contracts awarded by the US government only 23 contracts went to Haitian companies

- two US based private companies with strong US government connections – CHF International and Project Concern International – received an $8.6 million joint contract for debris removal in Port-au-Prince

- at a meeting of governments in Montreal in January 2011 the international community decided it was not going to allow the Haiti government to direct the relief and recovery funds

- an official report into the operations of the IHRC revealed that it failed to direct funding to projects prioritized by Haitians

Haiti Liberte was one of the first news sources to report the disaster relief ‘goldrush’ after secret cables by U.S. Ambassador Kenneth Merten were released by wikileaks in February last year.

Here is an example of the promotional material for one of the companies that won out in the scramble for contracts after the earthquake, United for a Sustainable America:

The horror. Renzo Martens eat your heart out.

The Haiti Liberte article also reported the story of Lewis Lucke, a 27-year veteran of the US Agency for International Development (USAID) who was named US special coordinator for relief and reconstruction after the earthquake. After a few months on the job he moved to the private sector, where he could sell his contacts and connections to the highest bidder. He quickly got a $30,000-a-month (plus bonuses) contract with the Haiti Recovery Group (HRG).

‘But in December 2010, Lucke sued AshBritt and its Haitian partner, GB Group (belonging to Haiti’s richest man, Gilbert Bigio) for almost $500,000. He claimed the companies “did not pay him enough for consulting services that included hooking the contractor up with powerful people and helping to navigate government bureaucracy,” according to the Associated Press. Lucke had signed a lucrative $30,000 per month agreement with AshBritt and GB Group within eight weeks of stepping down, helping them secure $20 million in construction contracts.’

According to an article written one year after the earthquake by Jordan Flaherty Gilbert Bigio made a fortune during the corrupt Duvalier regime and was a supporter of the right-wing coup against Haitian President Aristide. According to an article on Haiti Action Net, in 2007, after having doubled his fortunes since the ousting of Aristide, Bigio began building factories secured by armed guards and UN patrols in one of the poorest areas of Port-au-Prince, Cité Soleil.

A photograph from the GB website is uncannily similar to those bought by the plantation owner in Renzo Martens’ challenging exposé of the ethical paradoxes of global aid, photojournalism and contemporary art in the moral labyrinth of humanitarian aid work in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Enjoy Poverty III.

…artistic?

‘What can we do?’…use the ‘R’ word

The Counterpunch article ends its dismal inventory of aid relief and reconstruction failures for post-earthquake Haiti with a less than inspiring proposal of what can be done.

‘The UN Special Envoy to Haiti suggests the generous instincts of people around the world must be channelled by international actors and institutions in a way that assists in the creation of a “robust public sector and a healthy private sector.” Instead of giving the money to intermediaries, funds should be directed as much as possible to Haitian public and private institutions. A “Haiti First” policy could strengthen public systems, promote accountability, and create jobs and build skills among the Haitian people.’

Most of these proposals were made by many – including the author of the current article – immediately after the earthquake. Why would they be headed any more now than then? It’s also very worrying to see the ‘R’ word used in this context. It does not bode well.

The sudden ubiquitous use of the ‘R’ word in the language of British politics and social policy reached a peak during the summer riots here last year with politicians, newsreaders and political commentators all proclaiming the need for robust policing, robust sentencing and robust responses. It was a kind of memetic mania. How this word managed to find its way into so many mouths is a mystery. I random google search of ‘Robust UK Politics’ brings up calls from David Milliband for Labour to be ‘robust on Europe’, calls for a ‘robust voluntary sector work program‘, a ‘robust debate over jobs’ , a ‘robust climate change policy’, a ‘robust demand for gold bullion’, ‘robust Christmas sales’ and, my favorite, a ‘robust UK research climate’ .

Interestingly most of these uses occurred in 2011. A few, notably with reference to Gordon Brown’s ‘robust bullying’ and ‘robust survey of deaths in Iraq’ occurred a year or so earlier.

Isn’t ‘robust’ a meaningless, jargonistic, contemporary political euphemism for pretending to be doing something significant when actually you haven’t got a clue what to do? Or is there something more sinister at work here?

I can’t help being reminded of President Obama’s first statement following the Haitian earthquake: “I have directed my administration to act with a swift, coordinated and aggressive effort, to save lives”. Aggressive effort to save lives?

I will be discussing alternative approaches to what can be done about the situation at two events taking place at Occupy LSX next weekend. The first is an event taking place at the Bank of Ideas on Saturday January 14th about The Corporate Occupation of the Arts where I will be discussing protest pedagogy and the second an event organised by the London Occupy Economics Working Group called ‘Beyond Capitalism?’ on Sunday January 15th.

Scratch Edit of the Tap Tap Sign Video

Here is the scratch edit of the video I made during this year’s Ghetto Biennale. A final, subtitled version will be screened and exhibited along with the sign itself during 2012.

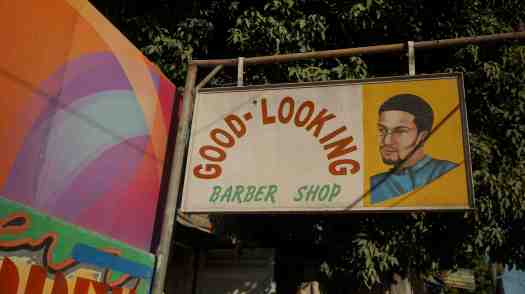

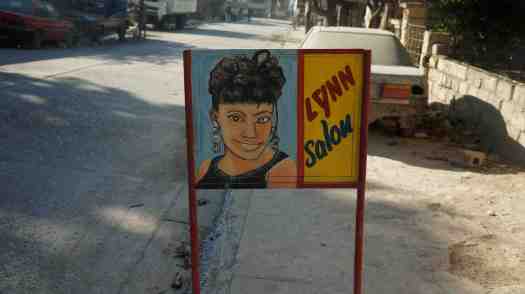

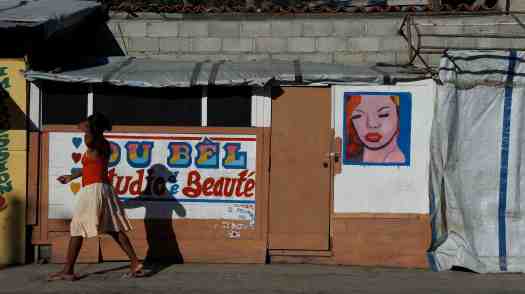

Barber Shop and Beauty Salon Signs in Port-au-Prince

Days 3 and 4

During the early negotiations about the painting for the tap tap it was proposed by Chevy that we should make the painting on vinyl so as not to damage the bonnet of Evel’s truck. The next day Michel and Joseph – the painters – suggested we make it on canvas so that after the biennale I can take the painting back to the UK. This is a brilliant solution. Alex printed off the new design he had made and the plan was to come back the next day to make the piece.

I arrived at the rue on Tuesday and painting began at about 9 o’clock. Here’s a sequence of stills from the process which I was also filming. The images are high-quality. If you double-click them you can see the detail.

Early stages. Drawing out the sign.

Early stages. Drawing out the sign.

The next day, after some confusion about where the canvas had been left, how it would be attached to the bonnet of Evel’s truck and the question of the sign for the front of the truck, Michel and Joseph arrived at Eugene’s yard with two signs on plastic they had made copying the lettering I had designed for the original Tele Geto postcard.

Today there is a memorial service and a procession to the cemetery for the members of the Grand Rue community who died during the earthquake. Eugene has proposed that Evel’s tap tap be used to lead the procession.