Here is the presentation and talk I gave at the Homo ex MachinAI conference in Athens on April 12th.

Thanks to Aspasia and Theo for all their hard work organising the conference and for inviting me to speak. Thanks also to the Benaki Museum for hosting such a timely and important debate. I will be speaking as an artist, writer and arts educator who has taught fine art studio practice and contextual studies for many years. I currently run the BA Fine Art and BA Fine Art with Psychology at the University of Worcester where I also lead the Arts and Health Research Group. I won’t be speaking about the latter today, but it informs my perspective on the impacts of generative AI tools on arts education and creativity more generally, particularly in relation to the mental and physical health effects of ubiquitous computing and on-line media environments within which generative AI developed and operates.

This is a list of the kinds of courses taught at a contemporary art school or university. It’s not comprehensive. It could include architecture, game art, interior and spatial design, printmaking, textiles and many others. The point is to show that ‘creativity’ is not a homogenous concept that can be generalised for all the arts. Every art has its own unique history, set of practices, understandings and outcomes. Because of this diversity, generative AI tools will not effect all teaching programs in the same way or to the same extent. Much depends on how teaching is tied to changes within the existing creative and professional fields it leads to.

Broadly speaking, teaching for professional fields already impacted by generative AI tools will be shaped most significantly. These include animation, commercial photography, film, game art, graphic design, journalism and marketing. This does not mean that learning traditional studio skills in these areas will become redundant. On the contrary, the successful artistic application of AI tools will depend on the technical experience, cultural knowledge and aesthetic discernment of its users. On the other hand, those arts more closely aligned with manual craft skills, individual authorship and the production of unique, physical artefacts made to be experienced in person, in real time and with all the senses, are less likely to be impacted as rapidly or significantly in the longer term. These include ceramics, dance, fashion, fine art, literature, performance, textiles and theatre.

The use of generative AI tools in an increasingly hybrid teaching environments, a trend amplified by the Covid lockdowns, will however be significant for all our programs. With students now regularly using AI-enhanced learning, research and writing tools, and universities moving towards AI-assisted grading and feedback systems, AI tools will play a transformative role in how teaching, administration and management in Higher Education is conducted, understood and regulated in the near future, regardless of what is being taught. I will be focussing here on my own field: Fine Art. Colleagues teaching in other areas will have their own particular stories to tell.

When prospective students visit the School of Arts at Worcester for Open Days I explain that Fine Art differs from other courses on offer in four interwoven ways. Firstly it is an explicitly studio-based discipline. Other programs use studios too, but students are not encouraged to inhabit their spaces quite as they do in fine art. The studio, I tell them, should be their second home. This has to do with the kind of objects they make. A painting, sculpture, performance or video installation is made to be seen IRL, to use the popular and telling acronym, rather than in print or on screen.

The essential value of fine artworks lies in their unique physical properties. Reflecting this, fine art courses culminate in a public exhibition of artworks in a gallery. There is an experiential continuity between the slow, individual process of creating unique, physical artefacts in a studio with the real-time experience of them, by others, in a gallery. This is the second unique characteristic of fine art.

Fine art teaching and studio practice is a communal experience through which students learn by making things together. This is supported by specific teaching methods: group crits (in which students collectively discuss and evaluate each others work), group workshops and lecture-seminars. Students are encouraged to reflect on their personal similarities and differences, and to understand the wider social processes that shape their collective and individual tastes and preferences. This collaborative and social mode of teaching and learning is fine art education’s third unique characteristic.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, fine art education involves a very personal journey of self-discovery, one supported by regular one-to-one tutorials. Unlike other visual arts disciplines, particularly those leading to commercial career paths in which students work to briefs modelled on those in their respective professional fields, the work created by fine art students is derived from their own enjoyment, desires, ideas, insights, interests, motivations, passions and preferences. It is a uniquely self-directed practice that flourishes by being free from overt, external constraints and demands.

These four characteristics, and the teaching methods that support them, lead to the development of what the authors of Studio Thinking: The Real Benefits of Visual Arts Education call “studio habits of mind”. It is my contention that these unique characteristics mean that fine art education is less likely to be transformed by generative AI tools than those fields more attuned to market forces, mass consumption, the logics of competitive self-interest and rational, data-driven, goal-seeking behaviour.

I would like to make a slight detour here about the impact of government educational policy in the UK, notably the prioritising of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) subjects in secondary schools and universities. This policy, developed as part of the government’s 2011 Plan for Growth, was designed to address a technical skills gap in the UK workforce. One consequence this has been a widespread devaluing of arts subjects amongst students and their parents, who often see art as frivolous and unlikely to lead to a lucrative career. This is not a new sensibility, especially for people from working class and minority ethnic communities. But the situation has worsened significantly in the last two decades. Public funding for the arts has been steadily decreasing over this same period and degree level arts courses are struggling to survive, particularly in higher education institutions outside major, metropolitan centres or established red brick universities.

The author’s of Studio Thinking experienced a similar challenge to arts education in the US in the 1990’s. Two of it’s authors, Lois Hetland and Ellen Winner, undertook a systematic investigation into claims made by arts educators that studying art help raise children’s exam results in other areas. Their research however discovered no causal evidence to support the claim. They did find that some students did well across both arts and science subjects. But this depended more on how much exposure they’d had to art and science at a young age than to any cognitive gain derived directly from art making. In other words, children who had what the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called the requisite “cultural capital” were more likely to get better grades across all subjects than those without. Initially the findings seemed to undermine the importance of studying art in schools but Hetland and Winner went on to complete a two year study of how art education does work and the benefits it brings to students. Studio Thinking was the result of that research.

To those not familiar with fine art education, it may seem that its ultimate aim is the production of artworks for exhibition. This is true. But it is only one side of the story. Alongside what we generally call studio practice is the study of art history, the philosophy of art, and a range of academic disciplines which we call ‘contextual’ or ‘critical’ studies. This is usually taught through lectures and seminars and culminates in the production of an academic dissertation. The ongoing critical reflection upon the nature, meaning and social function of art makes up a significant part of both fine art education and an artists life after graduation. It is however usually ‘invisible’ to the general public and partly explains why artists often have a different understanding of what art does and why.

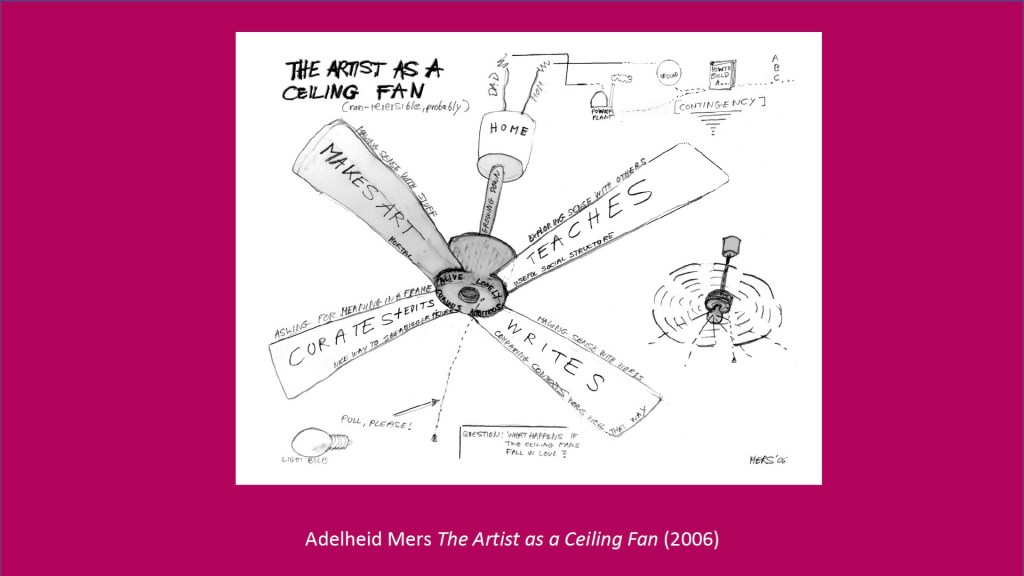

Shaped by avant-garde and revolutionary art movements in the early 20th century, the ideas that informed them and speculation about the function of art in society, contextual and critical studies gives fine art education an intellectual and political character. The artist Joseph Beuys is a good example of the kind of artist that emerged from the 1960’s, expanding his sculptural work to include his audiences, giving performance lectures, setting up alternative educational institutions and helping to create a political party. Today such activities form part of what many contemporary artists understand as their ‘practice’. Adelheid Mer’s image The Artist as a Ceiling Fan shows how the primary activity of making is complemented by teaching, writing and curating in a contemporary artist’s professional life.

Fine artists have been responding to technology since at least the beginning of the 20th century when they began reflecting on the environmental, psychological and social changes brought about by industrialisation, telecommunication and our relationship with machines. Each new development in technology, and the social environments they create, has been responded to in different ways by subsequent generations of artists, all building on the experience and innovations of their predecessors.

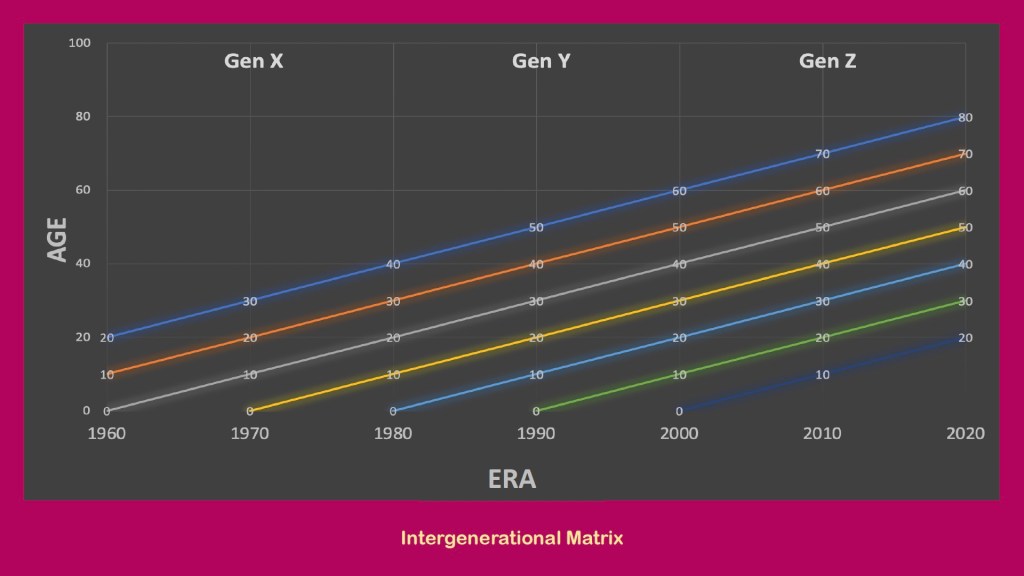

To help students understand the impact of technology on their perceptions and understanding of the world around them, I have developed a teaching diagram called the Intergenerational Matrix. The vertical axis represents an individual’s development through life from birth to death (i.e. one’s age) while the horizontal axis represents the historical timeline when each generation came into being. Thus a person born in 1960 will now be 64, having lived through all the changes that have occurred since then. They will share their world with everyone born after them and those, still living, born before. In such a world there can be no “one” understanding of the relationship between technology, consciousness and age, or any absolute, definitive perspective on their interwoven relationship. A comprehensive understanding of such complexity would require accommodating multi-cultural and multi-generational experiences and perspectives.

There are however some general truths. Most individuals evolve through similar biological and cognitive stages in life. Awareness of these changes does not become thinkable until we have developed motor skills, self awareness, learned to recognise objects, their names, numbers and symbols, acquired language, learned how to use logic, learned to problem solve and reached adulthood. But each generation grows within an evolving historical, social and technological environment. So being 17 in 1974 will be qualitatively different to being 17 in 2024. The older one becomes, the more experience one has to draw on, the further back in time one is able to imagine and the more experientially informed one’s understanding will be of the changes brought about by age. These insights helps us to begin a conversation about, and to think through, the continuities and differences of intergenerational experiences of art, aging and technology.

How new technologies are effecting developmental psychology is an urgent question for arts educators. Many of us have noticed an increasing emotional and informational dependency among students upon smartphones and tablets over the last two decades. A significant number of our students, at least in the first year of the program, are “glued to their screens” and have deeply engrained behavioural, cognitive and perceptual attitudes as a consequence. For us this is currently a more significant issue than the impact of generative AI tools. But given that it is within digital media environments that AI was born and is evolving, it is high likely that it will amplify and accelerate the behavioural and cognitive patterns already in evidence.

These are issues that Theo was working through in his paintings when we met in Oxford in 2017. I was already familiar with the early versions of text-to-image AI tools when I visited him in Athens in 2022 and he introduced me to Midjourney. Theo had been generating images that looked uncannily similar to his own work, notably the classical compositions and gestures, mix of artificial and natural light, and awkward, “not quite right” visual details. I was struck, as many have been, by the speed and quality of the images produced by Midjourney. But what intrigued me most was the ‘inner’ relationship between the language used in the prompts, how the AI translated them into images and the archives it was drawing on. Back in the UK I began playing with Midjourney and thinking about how to use it in my teaching.

The relationship between words and images is very important for arts education and has been approached from a wide range of disciplinary perspectives. In my teaching I use René Magritte’s famous painting The Treachery of Images to help students understand the essential difference between words and their referents, and by extension, objects and their images and paintings and their reproductions. Words, it shows, are merely conventional labels attached to objects and ideas in order to speak about them, and a digital reproduction of a painting on screen should not be mistaken for the physical artwork in a gallery.

I build on this basic lesson using a device created by the Polish mathematician and engineer Alfred Korzybski called a Structural Differential which extends Magritte’s example into the dimensions of space. It shows that the world is experienced by all the senses as change and flux prior to the perception, naming and identification of things. At each stage of abstraction, from the level of full, temporal and sensory experience to the zeros and ones of digital code, vast amounts of unrecoverable sensory information is lost.

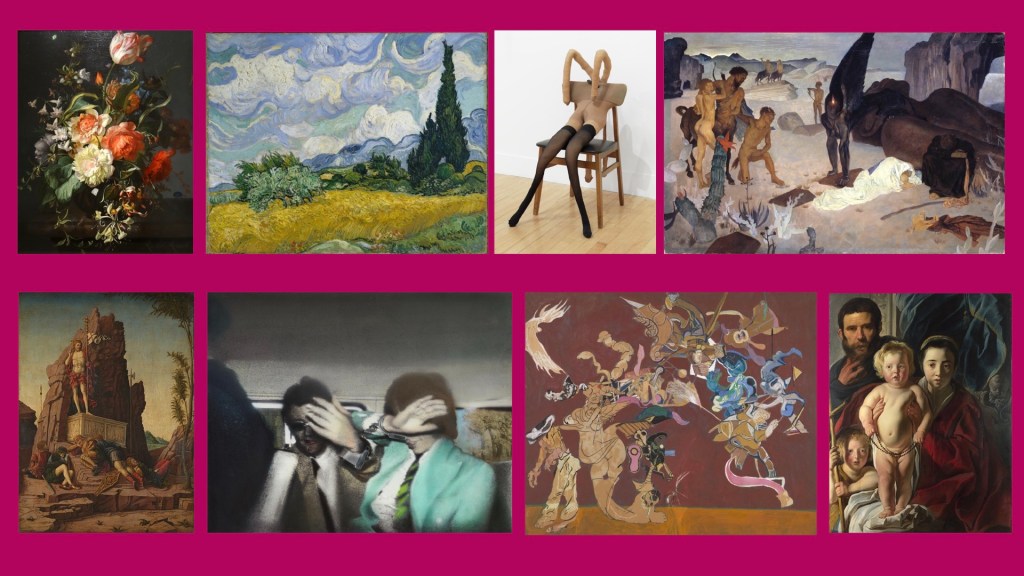

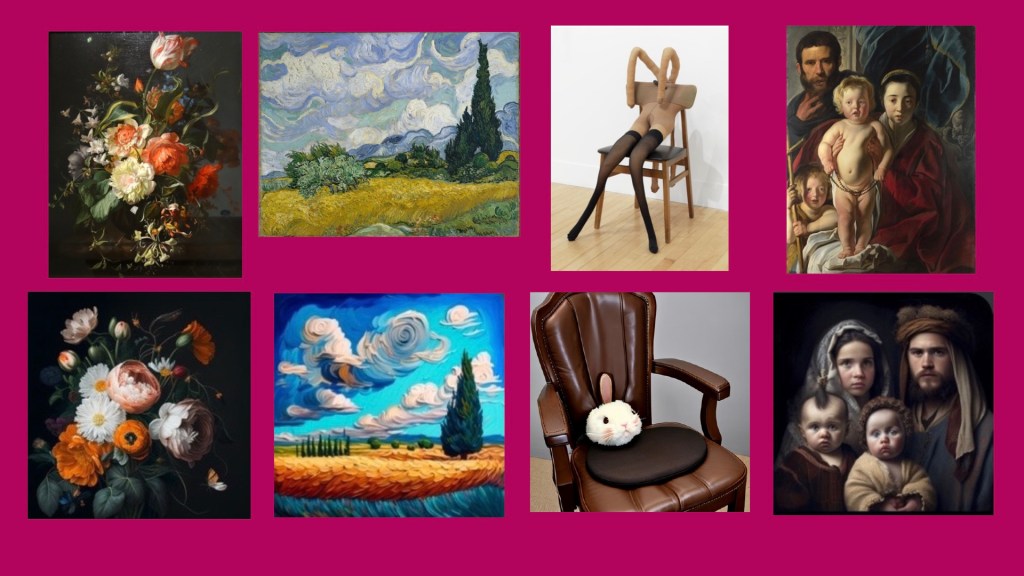

To deepen student understanding of these lessons, I set an assignment called Images for Interpretation. Each student is sent a different image from art history and asked to describe it in 300 purely descriptive words for someone who can’t see it. The descriptions are then shared with the rest of the group who create drawings based on them. After the first student has selected the drawing which comes closest, we collectively compare their description with the primary image and then make a group interpretation of it’s meaning.

I then set the students two tasks: i) reduce their description to 40 words and use it as a prompt for a text-to-image AI tool and ii) to set ChatGPT the same descriptive task I set them but including the title of the work and name of the artist. Students are then asked to reflect on the differences between the primary image and its visual translation by the AI and their own description and ChatGPT’s.

I’ve not been setting these exercises for long enough or at the kind of scale capable of generating enough data to draw conclusions about AI’s effectiveness as a teaching tool. As with most studio teaching, the feedback is subjective, circumstantial and unrecorded. From my limited experience of their responses however, students don’t seem to be either as impressed or concerned by the power of AI as colleagues. Some like the images it generates and keep them to share with friends. But they don’t consider them their own art. Others see it simply as “cheating”. Regarding the descriptions generated by ChatGPT, students have noted the use of flowery language, false facts, buzz words, inferences, speculative interpretations and a paradoxically subjective voice. This helps them understand that Chat GPT is neither looking at the same thing as them nor at any “thing’ in (the conventional sense of the word) at all.

In conclusion, I propose the following:

- The teaching profession has already been transformed by ubiquitous computing, automated administrative software, the use of online teaching platforms and research and writing apps. These changes will be accelerated and amplified by generative AI tools.

- The unique character of fine art education, the habits of mind it cultivates and the nature of the objects and events it creates are not readily reproducible or translatable into generative AI tools.

- Generative AI will impact the teaching of those arts more closely aligned with business, commerce, screen-based and print media than those that create unique, individually authored, physical artefacts and events designed to be experienced by humans with all their senses in space and time.

- Generative AI tools may have a valuable role to play in fine arts education, especially in terms of critical theory, digital literacy and philosophical reflection upon the nature of the arts in general.